Old Mathew had never married. Too shy, maybe? A spurned lover? Perhaps he was just ‘not the marrying kind’, as they used to say in a gentler, less intrusive, age.

He was not unaware of modern mores – his niece had been pregnant at a young age; the school bus driver it was rumoured. The scandal had bedevilled her young life, and she had never married either. She had inherited her parent’s small cottage, and lived a respectable life with her daughter. Old Mathew remained in the grand-parents home, and there had been little communication between the two families, living but yards apart, for many a moon.

Until a surprise letter arrived from a Solicitor in a nearby market town. Mother and Daughter knew that Mathew had died, found lying cold in his bed one January Sunday afternoon by concerned members of the local church – Mathew had never missed Sunday Service before. Mother and Daughter had viewed the funeral from the church gate, still outcasts after 25 years. There were no other relatives to see Old Mathew on his way; but still, old enmities die hard, and the funeral was no time to intrude into Mathew’s world.

Now I stood with Mathew’s great-niece, in the back yard of an old cottage deep in the Norfolk fens. She clutched the letter from the Solicitor, her passport to stand in this forbidden land.

We viewed the cottage from the yard. One half had totally collapsed: no roof, no chimney. A veritable pile of rubble. A pump and a bucket in the centre of the yard. A collection of outhouses, pig pens, chicken coops.

“Have you a key” I asked?

“No, it’s probably hidden somewhere” she said.

We tentatively pushed open the old latch doors to the outhouses. Some chickens rose up in alarm and scattered. We felt our way along dust covered beams, over doorways, in all the places that a key might have lay – nothing.

The back door didn’t look very strong, perhaps the bolt was rusty. “Shall I?” I said.

It wasn’t locked. There had never been a lock, rusty or otherwise. It was dark inside, and I fumbled for a light switch. I couldn’t find one. We stumbled towards the window by the light from the open door, and managed to pull back the old curtain, near rusted to its hook and wire fastening. The fabric was disintegrating as we tugged. Whoever had closed it had done so with great care – it was many years since that curtain was in service. Curtain is too grand a term, it was but a length of fabric, roughly sewn across the top, and the wire inserted into the envelope this provided.

There was the most terrible smell inside that room. Now with light, we could see why. Under a blackened beam across the one remaining chimney in that building stood an old range. I am not speaking of the sort of old fashioned Rayburn you might see in an abandoned railway cottage. I mean a really old, cast iron, range, the sort that Antique dealers ship to America for thousands of pounds. Above the range hung a collection of rabbits from wire hooks.

We remembered the old garden hoe we had seen in the outhouse and I ran out to get it; carefully unhooking each mouldering carcass, I slung them as far down the garden as I could. It marginally improved the smell.

Having refilled our lungs with fresh air, we ventured back inside. Now I could see why I hadn’t been able to locate the light switch – there wasn’t one. There was no electricity. Not just no electricity, but no running water either. The pump in the yard was the sole water supply.

The letter had instructed my young friend to see if she wanted any of the contents of the cottage before it was put up for auction. Old Mathew had left his entire estate to her, the estate that had once been his parents, the parents who had never spoken to her, the bastard child of their only daughter.

What contents? We looked around the single room – a solitary chair by the range, so worm eaten it would never survive the journey to the auction house. A table that had once been respectable, but the top had perished and been replaced with an old latch door. A rough wooden cupboard with two drawers. That was it, apart from a few enamel cooking vessels and some rusty tins above the cooking range.

We crept up the stairs, afraid at every step they would collapse. In the single room above, stood Mathew’s iron bed. On the back of the door, Mathew’s ‘Sunday suit’ – presumably he had been buried in the clothes he died in, there was nothing else, just a pair of working boots neatly stowed at the end of the bed. Oh, and a Bible on a night stand. In the corner of the room – several hundred apples, each carefully wrapped in newspaper. The bounty from the apple tree in the yard.

The sum total of Mathew’s possessions. Near 90 years of life on this earth, and the man owned nothing ‘cept that which was essential to his survival. Much later, a neighbour who had been present when his body was found returned the gun which had lived behind the door – taken for safekeeping since the cottage couldn’t be locked.

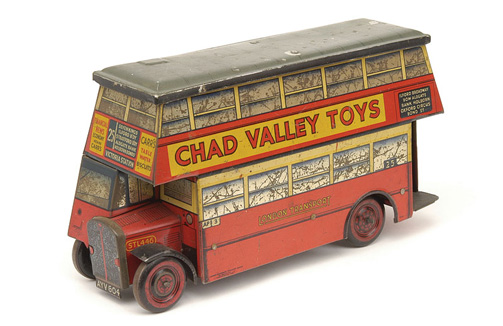

Before we left, I took down the rusty tins; they were an interesting shape, cars, buses, trams. I shook one, it rattled interestingly, but was so rusty I couldn’t open it there and then.

Now back at my house in a neighbouring village, we sprayed WD40 on the tins and managed to prise them open. Inside were dozens of small brown envelopes. Every tin revealed the same contents.

Pay packets, stretching back years, each one containing a crisp white fiver and a few coins. Coins that were long since out of circulation – as were the notes. We laid them out on the table – for each year there were approaching 50 envelopes, but always one two or three missing from the set. Almost £5,000 in total, in defunct English currency.

Eventually the Bank of England exchanged those notes, it took months. The cottage sold at auction. My friend’s Mother refused to have the rusty old tins in the house, they were thrown away. She bought an ultra smart sports car with the money – one in the eye for the village which had despised her and her Mother.

She sent me a newspaper cutting last week. An identical biscuit tin, not so rusty perhaps, had sold for £900! Just one of them. Mathew had a dozen of them.

Mathew had worked, he had a job in the local bakery; but he had not worked for the money. For pleasure? For Christian duty? Who knows? He had simply never felt the need to open his pay packets.

The nearby woods provided game, the yard gave him vegetables, the apple tree fruit; he had a set of clothes, a bible, and a range. He had never wanted more. His only connection to the modern world proved to be his demand for ‘rates’ every year, presumably the time when he reluctantly opened a pay packet. There were no other bills to pay.

Will people like Mathew ever exist again, men so utterly content with their existence that they remain detached from the materialistic world?

http://feedproxy.google.com/~r/AnnaRaccoon/~3/4stW1PbE1SU/

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.