Source:

“Inability to work following COVID-19 vaccination” is a modest paper just published in Public Health (paywalled, but available here as a preprint from last November), analysing data from the ‘CoVacSer’ cohort study, conducted out of Würzburg to monitor the effects of Covid infection and vaccination on healthcare workers. Of 1,831 CoVacSer participants who were surveyed on their experiences with vaccination between 29 September 2021 and 27 March 2022, 1,704 met criteria for inclusion in the present study. We’re looking therefore at the effects of the first, second and third doses.

From the abstract:

COVID-19 vaccination has emerged as a key strategy to control the spread and severity of SARS-CoV-2 infections, particularly among [healthcare workers]. However, vaccine-related incapacity could overwhelm public healthcare and must be addressed as part of this important prevention strategy. Vaccine-related staff absences must be considered in light of future COVID-19 booster vaccination campaigns and the challenges posed by the continuing COVID-19 pandemic.

The CoVacSer sample is overwhelmingly female (87%); only a minority (18.6%) were physicians. It is also relatively young and healthy, with a median age of 39 years.

The vast majority of everyone in the cohort received BioNTech/Pfizer for each of their three doses. Across all three doses and all 1,704 participants, the jabs resulted in a total of 1,550 sick days.

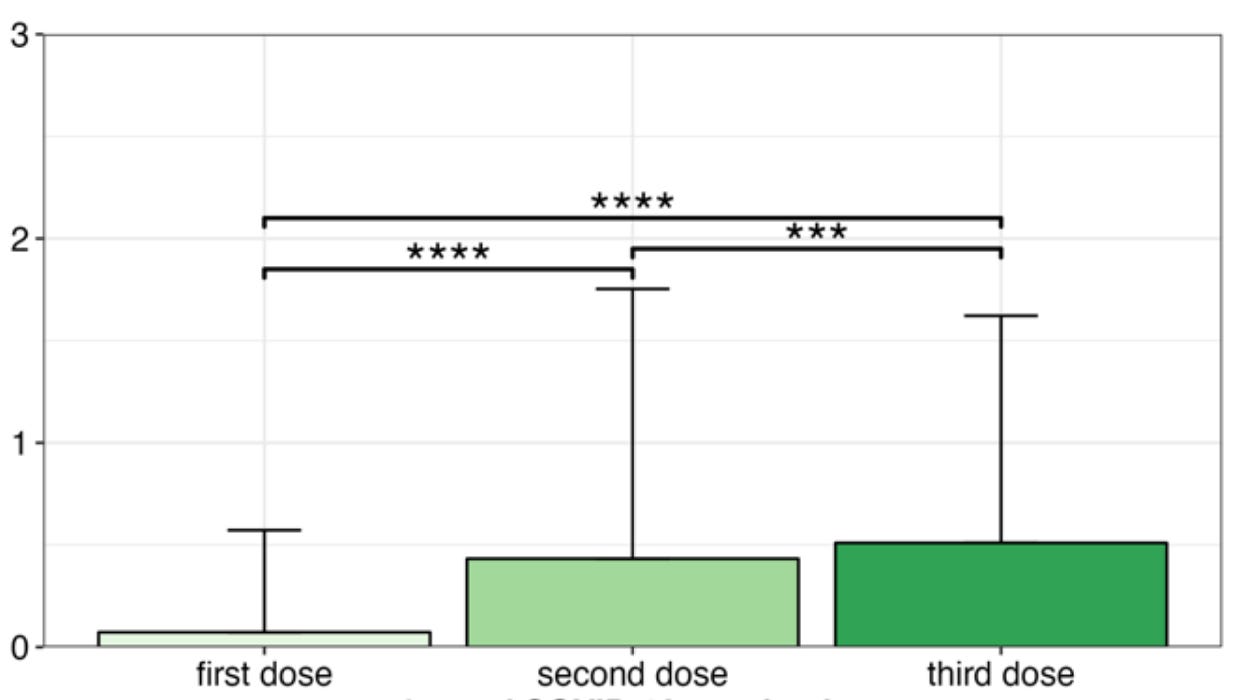

Here’s the chart of average sick days for each dose …

… and here’s the percentage of healthcare workers claiming some amount of sick leave for each dose:

Overall, the boosters resulted in 27.9% of the entire sample taking at least one day off of work. Of 21 participants who received AstraZeneca for their first dose, fully 11, or 52%, landed on sick leave. Moderna was also clearly worse than the BioNTech-determined average, sending 106 of 255, or 46%, of participants who received it as their third dose home for recovery.

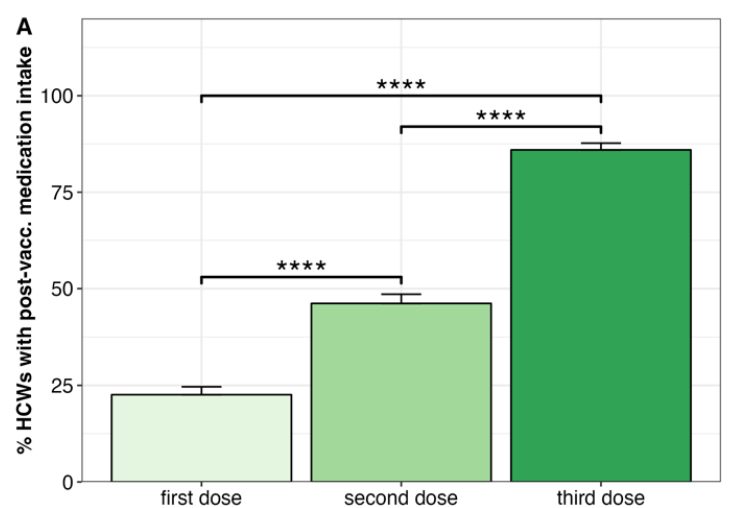

The broader subset of healthcare workers who took medication to relieve post-vaccination symptoms paints the same picture. By the third dose, the vast majority of everyone in the sample (86%) were taking drugs to relieve the acute symptoms of the jabs:

The gender breakdown is interesting: Males were less likely to take medication after the first and second doses (16.6% vs. 24% and 31.5% vs. 49.6% respectively), but by the third dose this gender difference disappeared. Men were consistently less likely to take sick leave after every dose, however.

The authors conclude that “COVID-19 vaccination has a non-negligible impact on the staff availability in the health sector” and that it is likely the enhanced immune response to each subsequent jab that is responsible for the escalating symptoms. We’re looking only at acute, immediate reactions to vaccination here – not at injuries or other more serious adverse events. The results of the study are clearly confirmed by the overwhelming disinclination of the general public to accept further vaccination after the booster campaign. Even when everything goes right, the vaccines make a lot of people feel sick, and the effect grows more pervasive and more powerful with each successive jab.

No comments:

Post a Comment

Note: only a member of this blog may post a comment.